Nearly 10 years after the signing of the Paris Agreement, a new energy investment paradigm is taking shape. Several key themes have emerged and can inform policy decisions aimed at addressing energy security, affordability, and competitiveness:

- The global energy investment landscape is at a potential inflection point as technical, market, and geopolitical dynamics realign. The rapid expansion of electrification and renewables is the defining legacy of the investment cycle that is now concluding, but low-emission sources are not yet able to fully replace the global hydrocarbon system. Rising demand complicates the outlook and reinforces an “all of the above” approach.

- Fragmentation, volatility, and scarcity are ushering in a new investment cycle while state intervention intensifies. Diverging policy priorities and deepening geoeconomic competition are reconfiguring trade flows, with bifurcating hydrocarbon and electric value chains aggravating the splintering of energy ecosystems. Higher interest rates, fiscal constraints, and capital access barriers are tightening financing and stimulating consolidation. Private capital markets could assume a larger role but have their own limitations.

- In this emerging paradigm, efficiency, security, and competitiveness trump decarbonization—though this does not mean low-emission energy will lose out. Renewables and fossil fuels can both be attractive in this pragmatic new normal. Aggregate growth will be resilient but uneven as energy pathways and capital strategies diverge. Beyond market fundamentals, investors will emphasize commercial readiness, localized needs, political alignment, and portfolio diversification.

- Proactive and coherent policy will be essential to align investment flows with strategic objectives amid elevated risks of capital misallocation. Market deficiencies will likely persist and widen funding gaps that exacerbate supply shortfalls and system inefficiencies. To translate national priorities into credible investment signals and stable enabling conditions, policymakers must leverage industrial policy, regulatory regimes, and trade measures in a coordinated and consistent manner.

The State of Play

A Historical Perspective

From biomass to the transoceanic hydrocarbons trade, the evolution of the global energy system has never quite been linear. Instead, it has ebbed and flowed through successive investment cycles, each shaped by the dynamic interplay of technical capabilities, market conditions, and political contexts. When these forces are in relative equilibrium, they can create stable investment environments that allow broad trends to emerge.

Following the commodities super cycle of the 2000s and the shale boom of the early 2010s, the 2016 Paris Agreement arguably marked the advent of one such cycle. Beginning to take shape in the late 2000s and peaking around 2021, this cycle was underpinned by an emerging global recognition of climate change and defined by record investment in low-emission energy, which is now nearly double global investment in fossil fuels, after surpassing it for the first time in 2016.

Entering the Electricity Super Cycle

Electricity demand is projected to rise through 2050 and meet a growing share of global energy demand. While per capita final energy consumption from fossil fuels has plateaued since the 1970s, electricity demand has steadily increased, nearly doubling since 2000. Between 2018 and 2023, electricity supplied more than 60 percent of the growth in final energy demand, compared with just 5 percent from hydrocarbons. On its current trajectory of around 3 percent annual growth, electricity could meet the entire increase in final energy demand by 2030.

Rising investment and technological advances—particularly in high-consumption sectors such as transport and heating—have expanded the technical potential and economic viability of electrification. Emerging end uses such as electric mobility, data centers, and advanced manufacturing are also further structurally entrenching electricity in energy demand growth. Data center electricity consumption alone, for instance, could increase from 500 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2023 to 4,500 TWh in 2050 globally and account for over half of total U.S. demand growth by 2030.

Mature Renewables Are Now Mainstream

The expansion of electricity capacity is increasingly powered by low-emission sources, many of which have outpaced growth projections. Renewable capacity has nearly doubled since 2015 and quadrupled since 2000 as technical advancement, learning by doing, and economies of scale made key technologies cost-competitive across many markets. Since 2010, the costs of onshore wind, batteries, and solar have decreased 70 percent, 83 percent, and 90 percent, respectively.

In 2024, renewables and nuclear energy met nearly 80 percent of global demand growth; wind and solar—the fastest-growing energy sources in history—accounted for 57 percent of the increase in electricity supply and over 90 percent of new grid capacity additions. In the United States, co-located and stand-alone solar and battery storage systems are expected to remain among the cheapest and fastest-to-deploy options, even as tax credits are rolled back. By 2050, renewables are forecasted to meet more than half of total global electricity demand.

Despite the momentum of electrification and renewables, phasing down fossil fuels is proving slower and more complicated than some anticipated. When paired with storage and transmission, intermittent or geographically constrained low-emission energy sources have demonstrated the ability to supplant fossil fuels at regional scales. Fully replicating the storable, portable, and tradeable characteristics of the global hydrocarbon system, however, still requires a scale-up of long-duration storage, low-emission and synthetic fuels, dispatchable firm power, expanded and flexible grids, as well as the requisite midstream infrastructure and enabling market mechanisms.

These systemic gaps help explain why the reduction in hydrocarbon consumption is expected to be staggered. Although total demand for oil and coal is trending downward through 2050, oil consumption is set to fall for road transport but rise for hard-to-abate sectors like petrochemicals, while coal use is projected to increase in emerging markets but decrease in developed countries. In contrast, natural gas demand could climb by as much as 25 percent over the same period, as it continues to provide flexible power and grid stability services in many markets.

New Challenges Driving a Paradigm Shift

Government Intervention Fueling Fragmentation

As energy becomes increasingly intertwined with national security and economic competitiveness, government intervention is catalyzing yet another transformation of the global investment environment. With geopolitical turbulence accentuating both vulnerabilities and opportunities associated with shifts in the energy system, countries are adopting more nuanced strategies instead of rigidly pursuing transitions or entrenching path dependencies. Namely, the global energy system is splintering along lines of resource endowment, industrial capacity, strategic priorities, geopolitical linkages, and growth pathways. In turn, trade protectionism, resource nationalism, and geopolitical fragmentation have intensified.

Splintering Energy Ecosystems

Although complex cross-border interdependencies will persist in the near term, a widening bifurcation between hydrocarbon and low-emission value chains—in part accelerated by strategic competition between the United States and China—is already reshaping global energy investment flows.

On one track are economies endowed with, or with secure and affordable access to, fossil fuels. Today, more than 50 countries meet over half of their primary energy demand with fossil fuel imports, but only one-quarter of countries worldwide are net exporters. With supply-demand balances remaining in flux, oil and gas prices are expected to remain volatile, contributing to uneven capital deployment across the sector. While lower oil prices and rising costs have triggered a drop in upstream and refinery investment, a surge of new liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects is due to expand export capacity by one-third by 2030. Notably, the United States has emerged as a major producer and exporter of oil and LNG. This shift coincides with—and in some ways reinforces—the country’s retreat from its postwar role as the facilitator and guarantor of global trade.

On the other track are economies turning to electrification and renewables as engines of supply security, domestic value creation, or climate goals. Emerging economies have become quick followers in this category. Nearly 90 percent of capital expenditure (CAPEX) on energy generation in the Global South funded low-emission sources in 2024, up from just under 50 percent 10 years ago. More than 60 percent of countries in the Global South have surpassed or are on track to overtake their Global North counterparts in renewable penetration; 80 percent have done so for electrification. Driving this shift is China, which has led the world in supply chain and manufacturing investment—both domestically and, increasingly, overseas. It currently supplies over 70 percent of batteries, 80 percent of solar components, and over 90 percent of rare earths processing capacity.

Macroeconomic Headwinds

Geopolitical pressures and policy uncertainties are aggravating an already shaky macroeconomic outlook. Global GDP growth is projected to decelerate to an average of 2.6 percent from 2025 to 2028, the lowest level since 2008 and weaker than the 3 percent average over the last 15 years. At the same time, the monetary environment is expected to be tighter in the near to medium term as interest rates stay higher for longer after the most aggressive hiking cycle in decades. Nominal and real interest rates in major economies could, on average, be up to 2 percentage points higher over the upcoming decades than they were from 2009 to 2022.

The capital intensity and return profile of low-emission technologies make them especially sensitive to higher rates. While extractive industries can be better insulated from rate hikes, they are nonetheless exposed to second-order effects of trade restrictions and policy uncertainties, which have put downward pressures on GDP, income, and trade growth while driving up inflation expectations. Coupled with rising debt levels, higher borrowing costs could compound fiscal constraints and limit government discretionary spending on energy. Developing economies—already contending with structural deficits ranging from sovereign and currency risks to shallow domestic capital markets—are more vulnerable to tariff uncertainties and foreign currency losses.

Public Markets Under Strain

The convergence of these pressures could exacerbate liquidity constraints in public capital markets, where the performance of exchange-traded energy firms continues to shape financing flows. In recent years, cost overruns and delays—driven by higher cost of capital, supply chain disruptions, and policy uncertainty—have eroded operating margins for renewables, in turn dampening equity performance and restricting capital access. In parallel, oil and gas companies have prioritized debt repayment, share buybacks, and dividends over CAPEX expansion despite their lower sensitivity to borrowing costs. Even with stronger market performance and higher free cash flow in recent years, CAPEX decisions of oil and gas majors will likely remain anchored in business fundamentals rather than policy shifts.

Private Markets Double Down

If public equity markets and bank lending remain constrained, private capital markets could assume a more significant role in energy investment. Despite liquidity and cost of capital disadvantages, private credit, equity, and other alternative strategies can offer lower exposure to market sentiments or predictable cash flows—appealing to investors and developers seeking financing suited to energy and utility assets. As fossil and renewable majors streamline their holdings and AI data center demand surges, opportunities for private markets are expanding; major North American utilities, for instance, are increasingly funding new CAPEX by selling minority stakes to private equity.

Owing to a greater flexibility to structure bespoke transactions, private markets have enabled low-emission energy technologies that historically fell outside bank lending parameters, while strong performance has sustained investor interest. Low-emission investments saw a compound annual growth rate of 17 percent since 2019 in private markets, compared to 11.9 percent in public markets. At 123 percent, the reported cumulative returns from these portfolios more than doubled the 57 percent return of their public counterparts. Within private funds, renewables also outperformed fossil fuels on their internal rate of return between 2016 and 2023, though the gap has recently narrowed.

Settling into a New Normal

As the ever-tenuous climate consensus further fractures, expectations of the “green premium”—in the form of financial returns or strategic value—that shaped investment in the past decade has deteriorated. In its place, a new energy investment paradigm is emerging amid heightened volatility, fragmentation, and scarcity. Globally, considerations of economic efficiency, energy security, and national competitiveness have overtaken climate mitigation—as an end in itself—as the more immediate forcing functions shaping investment decisions. With anticipated demand rising, near- to medium-term investments will prioritize the delivery of usable power.

Yet these shifts do not imply that low-emission energy sources will fall behind. On the contrary, they have strong potential to thrive under these new priorities. Aside from being among the fastest and cheapest capacity to deploy globally, low-emission energy sources can advance national priorities ranging from energy independence to industrial growth. Around 80 percent of global non-hydro renewable capacity added since 2010, for instance, has been in countries reliant on fossil imports. As geopolitics retakes center stage and governments play a more active role in shaping energy investments, historical precedents underscore this potential: The oil crises of the 1970s were accompanied by a drop in fossil fuel consumption on par with that during the Paris era.

Resilient Investment Drivers

As these shifts unfold, the emerging energy investment environment is dynamic but fragmented; though growth opportunities are widespread, risk assessment and investment decisions will vary depending on dynamics within specific markets. With commercial sources of capital financing almost 75 percent of global energy investment, an understanding of the factors shaping these investment decisions is crucial for policymakers. While fundamentals—cost of capital, cash flows, and expected returns—will remain decisive, capital allocation will increasingly hinge on commercial readiness, local system needs, alignment with political priorities, and portfolio diversification value.

Commercial Readiness Reigns Supreme

Over 90 percent of low-emission energy investment to date has flowed into technically and commercially mature solutions, which could further move down the cost curve as global manufacturing scales up and innovation iterates. The influx of risk-averse capital suggests that mature renewables are now viewed as mainstream investment opportunities rather than niche plays. Debt and project financing for low-emission technologies have surged—at a 49 percent compound annual growth rate since 2019—even as the capital mix of the entire energy sector has stayed relatively stable at around 45 percent debt to 55 percent equity for the past decade. Wind, solar, and batteries constituted nearly 80 percent of all U.S. power sector project finance deals in 2024; debt also financed 80 percent of global utility-scale solar and wind additions, up from 56 percent in 2015.

Going Local

Similarly, localized system needs are becoming central to investment decisions. In many markets, grid reliability and resilience are emerging as the most pressing consideration instead of the cheapest unit of generation. As a result, market-specific factors including interconnection status, import dependence, and price sensitivity are increasingly shaping investment priorities more than marginal cost. Rising interest in projects that alleviate grid bottlenecks, expand transmission capacity, or provide ancillary services reflect broader investor recognition of system-level dynamics alongside project-level returns.

Catering to Policy Priorities

Energy investment opportunities perceived to align with broader state priorities—such as securing supply chains, fostering technology leadership and domestic industries, and reducing climate change exposure—will remain attractive, though their contours will vary across jurisdictions (see Box 2). Aside from the potential to access government incentives, investors are increasingly prioritizing the “certainty premium” associated with political support and regulatory clarity in a volatile macroenvironment. To capture this premium, some investors might be more willing to commit long-term capital to projects with strategic resonance, even when financial advantages are modest. Conversely, existing momentum in the form of industry standards or committed capital could reinforce path dependency even when investments are temporarily out of step with policy priorities.

Diverging Policy Trajectories Create Diverse Opportunities

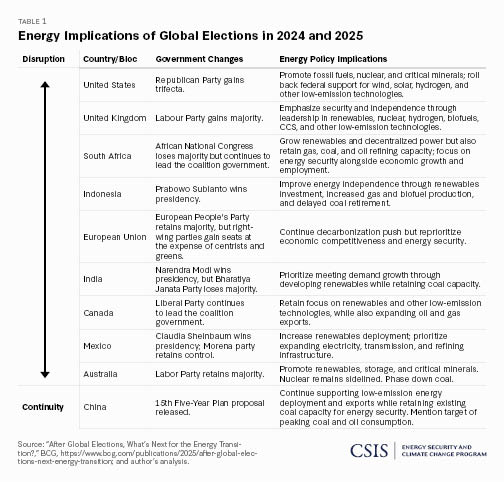

Recent policy shifts in the aftermath of global elections reflect the diversification in investment opportunities. The European Union, for instance, is moderating from an aggressive decarbonization drive to rebalance for energy security and industrial competitiveness. In contrast, the United States has retreated from climate leadership in favor of fossil fuels abundance and trade protectionism. China, on the other hand, has deepened its commitment to renewables manufacturing and exports while maintaining coal capacity. As major economies pull in different directions, allied and nonaligned states alike will also adjust their approaches—potentially by diversifying trade relationships to hedge against overreliance.

Rethinking Portfolio Diversification

To better capture value amid contradictory policy signals and uneven market conditions, investors are turning to diversified portfolios that hedge capital-intensive assets with stable, contracted cash flows against those with higher marginal costs and greater exposure to commodity prices and merchant power markets. Since both fossil fuel and low-emission energy can fit either profile, technology distinctions matter less than the differences in cash flow profiles and financing structures.

Fixed-return assets gain value when interest rates stabilize and borrowing costs are low, while market-linked assets can outperform during periods of inflation and elevated energy or commodity prices. Effective diversification strategies will hinge on managing this countercyclicality across rate and price cycles rather than uniformly favoring certain energy sources. If supply chains and policy priorities continue to splinter, portfolio diversification strategies will further drive divergent investment opportunities across jurisdictions.

Implications for Policymakers

As investors acclimate to new structural realities of the emerging energy investment paradigm, capital strategies are becoming more diversified and selective. Policymakers need to remain vigilant: Even if aggregate energy financing volumes stay robust, market incentives alone may not align seamlessly with socially optimal outcomes or strategic objectives. Left unaddressed, such misallocations could exacerbate supply shortfalls and system inefficiencies that undermine energy security and affordability.

Clarity on Market Deficiencies

Strategic companies, projects, and industries frequently lack the risk-return profile to attract sufficient private capital. Even when interest exists, markets often fail to deliver a fit-for-purpose capital stack—from grants and concessional finance to equity and commercial debt—in the right sequence to enable deployment; higher-risk innovations are particularly vulnerable to these “valleys of death.” Enabling infrastructure elements, such as transmission lines and gas pipelines, face similar hurdles as their diffuse benefits are essential for system reliability and capacity expansion but can be challenging to monetize.

These financial and structural frictions are compounded by the complex, cross-border supply chains on which energy systems depend. Sectors dominated by foreign incumbents can face path dependencies that deter domestic investment and innovation. Conversely, abrupt localization efforts—such as prematurely restricting imports or knowledge transfers—can trigger immediate supply shocks and impede capacity-building. Similarly, undue regulatory burden or policy uncertainty could erode investor confidence and deter capital flows to activities that are otherwise both commercially attractive and strategically important.

Strategic Policy Interventions

Addressing these market deficiencies will require a clear and coherent approach to economic statecraft, as policy stability and consistency have become competitive advantages in their own right. Policymakers must be able to articulate and implement long-term strategies that harness industrial policy, regulatory regimes, and trade measures in concert. To ensure that they enhance, and not distort, market dynamism, these policy interventions must be fit-for-purpose and grounded in a nuanced understanding of specific dynamics shaping each industry of interest.

In addition, policymakers should leverage public financing authorities—among the most direct means of translating policy intent into tangible investment outcomes—to bridge capital gaps and mitigate market volatility through instruments such as contracts for difference, risk underwriting, or offtake agreements. Coordinating the efforts of these authorities—whether they are domestically oriented or internationally focused—helps strategic projects and industries across geographies access the appropriate form of capital at each stage of development.

Ultimately, the policy challenge ahead is pragmatic rather than ideological. While effective governance can take many forms, investors are gravitating toward jurisdictions able to combine strategic clarity with consistent execution. The operative task for policymakers, therefore, is to translate national priorities into credible market signals and enabling conditions. With industrial policy and other forms of state intervention experiencing a global resurgence, governments that adapt proactively to the emerging energy investment paradigm will be best positioned for long-term competitiveness.